Justice Department Attempts to Suppress Evidence That the Border Patrol Targeted Humanitarian Volunteers

Four volunteers with

a faith-based humanitarian group drove onto a remote wilderness refuge

in southern Arizona last summer hoping to prevent an unnecessary loss of

life. A distress call had come in, a woman reporting that two family

members and a friend were without water in one of the deadliest sections

of the U.S.-Mexico border. For hours, the volunteers’ messages to the

Border Patrol went unanswered. With summer in the Sonoran Desert being

the deadliest time of year, they set off in a pickup truck, racing to

the peak where the migrants were said to be.

Once on the refuge, the volunteers were tracked by federal agents, beginning a process that would lead to federal charges. Now, more than a year later, they each face a year prison, and Trump administration prosecutors are fighting to keep the communications of law enforcement officials celebrating their prosecution from becoming public.

The legal wrangling began this week, when the volunteers’ attorneys filed a series of motions urging Arizona Magistrate Judge Bruce G. Macdonald to dismiss the charges against them, citing allegations of selective enforcement and violations of international law, due process, and religious freedom. Attached to the motions were several exhibits, including text messages between federal law enforcement officials. Justice Department attorneys quickly moved to have the motions sealed, but not before The Intercept downloaded them from Pacer, the public-facing repository for federal court records.

Once on the refuge, the volunteers were tracked by federal agents, beginning a process that would lead to federal charges. Now, more than a year later, they each face a year prison, and Trump administration prosecutors are fighting to keep the communications of law enforcement officials celebrating their prosecution from becoming public.

The legal wrangling began this week, when the volunteers’ attorneys filed a series of motions urging Arizona Magistrate Judge Bruce G. Macdonald to dismiss the charges against them, citing allegations of selective enforcement and violations of international law, due process, and religious freedom. Attached to the motions were several exhibits, including text messages between federal law enforcement officials. Justice Department attorneys quickly moved to have the motions sealed, but not before The Intercept downloaded them from Pacer, the public-facing repository for federal court records.

Read Our Complete CoverageThe War on Immigrants

Read Our Complete CoverageThe War on Immigrants

The exhibits include text messages between a U.S. Fish and Wildlife

Service employee and a Border Patrol agent, in which the Fish and

Wildlife employee declares “Love it” in response to the prosecution of

the volunteers. Described in the text messages as “bean

droppers,” volunteers with the group No More Deaths and their

organization are referred to by name in the communications between

federal law enforcement officials, who describe, with apparent glee, the

government’s “action against them.”

Within

hours of the exhibits being submitted Monday, Trump administration

lawyers called on Macdonald to seal the text messages, on grounds that

they contain “sensitive law enforcement information.” The government

prosecutors also requested the sealing of a blank Fish and Wildlife

permit application — available online — and documents turned over via a

Freedom of Information Act request, citing the same justification.

Attorneys for the defendants then filed an opposition motion, arguing

that the government’s descriptions of the materials “strain credulity.”

The U.S. Attorney’s office in Arizona and the Border Patrol’s Tucson

sector declined to comment on the motion to seal and claims made by the

defendants’ legal team, citing the ongoing nature of the case.

Within

hours of the exhibits being submitted Monday, Trump administration

lawyers called on Macdonald to seal the text messages, on grounds that

they contain “sensitive law enforcement information.” The government

prosecutors also requested the sealing of a blank Fish and Wildlife

permit application — available online — and documents turned over via a

Freedom of Information Act request, citing the same justification.

Attorneys for the defendants then filed an opposition motion, arguing

that the government’s descriptions of the materials “strain credulity.”

The U.S. Attorney’s office in Arizona and the Border Patrol’s Tucson

sector declined to comment on the motion to seal and claims made by the

defendants’ legal team, citing the ongoing nature of the case.

In addition to the exhibits the government would like to have sealed, the motions filed this week provide the latest evidence that law enforcement actions taken against No More Deaths, an official ministry of the Unitarian Universalist Church in Tucson, are part of a campaign targeting the organization. In a sworn declaration, Robin Reineke, a cultural anthropologist and director of the Colibrí Center for Human Rights, an internationally renowned organization that repatriates the remains of migrants who die in the desert, described a meeting last summer in which a senior Border Patrol agent angrily told her that because of the bad press No More Deaths stirred up for his employer, the agency’s plan was to “shut them down.”

In an interview with The Intercept on Wednesday, Reineke described the meeting as “disturbing,” saying it spoke to a broader breakdown between nongovernmental organizations responding to the humanitarian crisis on the border and federal law enforcement, including a Border Patrol workforce emboldened by an administration set on pushing an already punishing immigration enforcement apparatus into overdrive.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service itself describes Cabeza Prieta as “big and wild” and “incredibly hostile to those that need water to survive,” with a “56-mile border with Sonora, Mexico, [that] might well be the loneliest international boundary on the continent.” According to the Office of the Medical Examiner in Pima County, 33 sets of human remains were found on the refuge last year alone, adding to the more than 8,000 sets of human remains found along the border since the U.S. government began funneling migrants into the desert over two decades ago.

In the case in question, four No More Deaths volunteers — Caitlin Deighan, Zoe Anderson, Logan Hollarsmith, and Rebecca Katie Grossman-Richeimer — say they were doing everything in their power to prevent that grim toll from expanding when they were targeted by law enforcement.

On July 19, No More Deaths received a distress call from a woman in Phoenix reporting that two of her cousins and a friend were in need of help on the refuge. Volunteer Jesse Ferrell filled out the intake form. The woman told Ferrell that the group had built a bonfire to attract help the previous night and that by the following morning, they had run out of water. The men called the Mexican consulate in Tucson, the woman said, and were told to call 911. They did so, she added, but were told by the operator that nothing could be done. They would need to communicate with an immigration-specific office.

In Arizona, the Border Patrol’s Missing Migrant Initiative requires 911 dispatchers to transfer calls from migrants in the desert to a Joint Intelligence and Operations Center in Tucson. For years, the MMI program has been managed by two agents in the Border Patrol’s Tucson sector: Mario Agundez and Pedro Alonso Jr. The documents submitted in court this week show Ferrell first emailing Agundez at 1:57 p.m., then again roughly a half-hour later, at which point Agundez was told that the migrants were at a well-known peak as recently as the previous night, and that they were out of water. The email thread indicates Agundez first responded to No More Deaths more than seven hours after the group’s initial email was sent.

According to Reineke, slow responses to distress calls have become standard with the Border Patrol, and with Agundez specifically. In the declaration she submitted this week, Reineke explained that in years past, her organization “worked closely” with agents from the Border Patrol’s Search, Trauma, and Rescue teams, otherwise known as BORSTAR. “Over time, however, we learned that BORSTAR was generally unresponsive to calls for distress,” Reineke said. “Even in cases of a distressed migrant who had been seen within an hour of the rescue call.”

It was the same in cases where Border Patrol was provided a map of the migrant’s last known location, Reineke added. “BORSTAR would not initiate search and rescue operations — at times affirmatively denying the request to us in writing, and at other times simply not responding to the request.” Based out of the Office of the Medical Examiner in Pima County, the team at Colibrí stopped forwarding distress calls to BORSTAR in 2015, Reineke said, in part because of a “particularly poignant” case in which Agundez reportedly refused a desperate wife’s request to initiate a search for her husband.

In place of BORSTAR, Reineke said, Colibrí began forwarding its distress calls to No More Deaths. Recently, she explained, she has observed a marked change in the Border Patrol’s treatment of the organization. On June 12, 2017, the Border Patrol raided a camp that No More Deaths has used to provide medical aid for migrants for more than a decade, following a tense three-day standoff and leaving with five undocumented men it had tracked to the location in tow. As The Intercept reported at the time, No More Deaths volunteers saw the operation as a message from the Border Patrol that things would be different under the Trump administration. Reineke happened to have a prescheduled meeting with Agundez and his partner, Alonso, a week after the raid took place.

“I expressed my anger and dismay that agents would raid a humanitarian aid station in the desert during a heatwave,” Reineke said in her declaration. Agundez’s response was “angry” and “defensive,” she said. “He referred to the negative press against the Border Patrol generated by No More Deaths, and said they had ‘gone too far,’ that ‘they have messed with the wrong guy.’” Reineke added, “He told me the agency had intentions to ‘shut them down.’”

In an interview Wednesday, Reineke told The Intercept that she had called for the June 21 meeting with Agundez and Alonso Jr. after receiving upsetting reports from officials at two Latin American consulates that the Border Patrol had been discouraging them from cooperating with Colibrí. It was in that tense context, Reineke said, that the Border Patrol’s raid on the humanitarian aid camp came up. Agundez’s response left Reineke with a clear impression. “My impression was hostility to No More Deaths,” she said.

“I got a really strong sense of retribution, revenge — he didn’t like what No More Deaths was saying to the press about Border Patrol,” she added. “I really got the strong impression that he wanted to see the camp shut down and gone.”

More than five months would pass before the government formally charged the group with federal misdemeanors related to unauthorized driving and entering the refuge without a permit. Ultimately, two of the migrants reported missing were found by a pair of Border Patrol agents stationed in Ajo, Arizona, and a Yuma-based Customs and Border Protections helicopter crew that established communications with the No More Deaths volunteers. The third individual was never found.

Although charges were not brought for months, Cabeza Prieta officials did not waste time in flagging the No More Deaths volunteers as troublemakers. According to internal communications obtained by The Intercept via a Freedom of Information Act request, Mary Kralovec, then-assistant refuge manager at Cabeza Prieta, sent an email to colleagues and counterparts at the Fish and Wildlife Service and the Air Force (which manages the nearby Barry Goldwater bombing range), the day after the rescue operation, highlighting the four volunteers as “individuals who we are not issuing access permits to.”

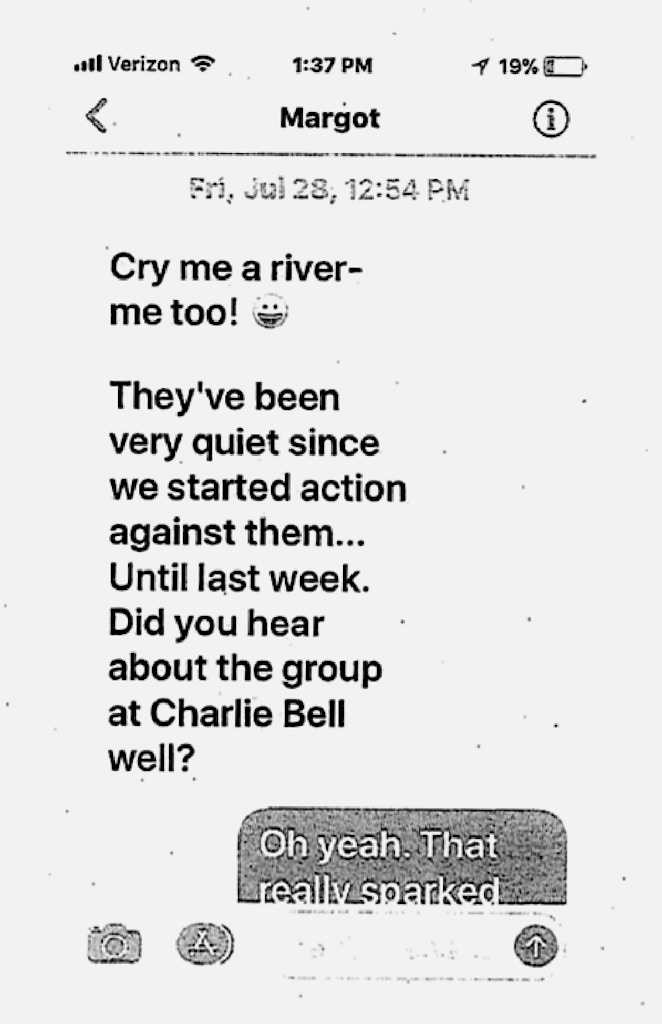

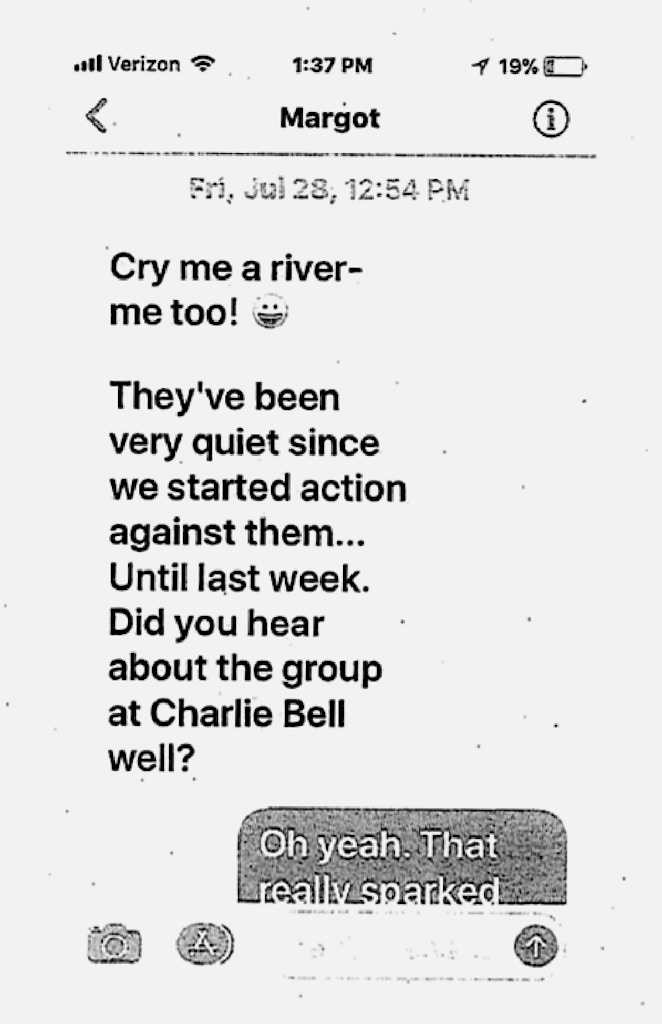

A little more than a week later, on July 28, Margot Bissell, a visitor services specialist at Cabeza Prieta, began sending a series of text messages that are now at the center of the disclosure fight in the No More Deaths volunteers’ case. According to the motions filed this week, Bissell’s messages were sent to a Border Patrol agent who at this point remains unnamed. The exchange begins with Bissell writing, “Cry me a river – me too,” followed by a laughing emoji. While the context of the comment is unclear, the following message is not.

“They have been very quiet since we started action against them … Until last week,” Bissell wrote. She then asked, “Did you hear about the group at the Charlie Bell well?” — referring to the location where the No More Deaths volunteers were encountered.

“Oh yeah,” the agent replied. “That really sparked everything back up.”

“Love

it,” Bissell wrote. “One lady was arrested, trying to tear the camera

off! Oh my gosh! Then she went down there again! The next day.” Three

days later, the agent wrote again: “Let me know of [sic] anymore [sic]

bean droppers come around”. Having recently returned to work, Bissell

wrote that she “heard 8 of them showed up last week wanting permits. 3

of them were on the do-not-issue list.”

“They acted so surprised,” she wrote, adding a frowning emoji. The

agent said they would “try to figure out who they are.” Bissell

responded by providing the two names she had. “Heard we are pressing

charges against Scott Warren,” she added. The agent said they heard the

same. Months later, in October, Bissell messaged again. “They’re

baaaack….!” she wrote. “A ton of No More Deaths last two days in here

getting permits.”

“Love

it,” Bissell wrote. “One lady was arrested, trying to tear the camera

off! Oh my gosh! Then she went down there again! The next day.” Three

days later, the agent wrote again: “Let me know of [sic] anymore [sic]

bean droppers come around”. Having recently returned to work, Bissell

wrote that she “heard 8 of them showed up last week wanting permits. 3

of them were on the do-not-issue list.”

“They acted so surprised,” she wrote, adding a frowning emoji. The

agent said they would “try to figure out who they are.” Bissell

responded by providing the two names she had. “Heard we are pressing

charges against Scott Warren,” she added. The agent said they heard the

same. Months later, in October, Bissell messaged again. “They’re

baaaack….!” she wrote. “A ton of No More Deaths last two days in here

getting permits.”

“Sweet,” the agent replied. “You got any new info or names.” Whether Bissell replied is unclear.

An email to Bissell’s work address seeking comment on her texts generated an out of office reply. Her supervisor, Sid Slone, did not respond to a request for comment.

The disclosure of the text messages comes three months after The Intercept was first to report on a series of communications and internal reports between Border Patrol agents involved in Warren’s felony arrest. Those materials included talk of an open investigation into No More Deaths as an organization and cited the raid on the No More Deaths camp that Agundez referenced with Reineke as the beginning of that effort.

The inclusion of those communications in pretrial motions, which also included law enforcement text messages, angered Trump administration attorneys: In the words of one individual close to the case, the government’s attorneys were “fucking pissed.” The prosecutors successfully lobbied to have the materials sealed after The Intercept reached out to Justice Department for comment, but before the article was published.

“None of these incidents were referred for prosecution or prosecuted, except for those involving No More Deaths volunteers,” the attorneys noted, including the four defendants cited in connection with last summer’s search and rescue operation.

Other groups that do search and rescue work were not similarly cited, the lawyers added. The difference between No More Deaths and those organizations, they argued, is that No More Deaths publicly critiques the Border Patrol and U.S. border enforcement policies. “Thus,” attorneys for the volunteers contended, the Fish and Wildlife Service’s “own records indicate that defendants were subject to enforcement action as a result of their affiliation with an organization speaking out against the government’s immigration policies and conduct.”

Last summer, as the number of remains recovered on Cabeza Prieta reached record highs, land managers tweaked permit applications for the refuge, requiring applicants to explicitly agree to not leave food, water, or clothing on the refuge. No More Deaths saw the change as a direct attempt to undermine their efforts to provide lifesaving aid in a place where people are clearly dying. Their attorneys say the change was illegitimate, arguing that the land managers failed to publish the new permit language in the federal register, “nor was it subject to public notice and comment procedures as required by the Fish and Wildlife Service Manual and the Code of Federal Regulations governing the Service’s rulemaking.”

The enforcement of permitting rules stemming from “illegally-amended language” against No More Deaths volunteers alone amounts to violation of an international smuggling protocol the U.S. ratified in 2005, the attorneys say. The protocol requires that the state cooperate with nongovernmental organizations “in protecting and preserving the human rights of smuggled migrants,” the attorneys noted. But it goes deeper than that, they argued. By seeking to imprison a group of humanitarian volunteers over their efforts to save three people in the desert, the state had entered into dark territory reserved for the worst regimes, the attorneys contended.

“Common decency requires that a government do what it can to prevent unnecessary death and suffering inside its borders,” the lawyers argued in the motions filed this week. “To actively thwart efforts of its citizens to assist those in need through the provision of the most basic necessities — emergency food and water — is cruel and shameful behavior. And to threaten to imprison citizens for searching for distressed migrants stranded in highly dangerous locations — generous, humane actions the government should encourage and applaud — is unconscionable. It violates the universal sense of justice.”

In the southern Arizona, a place with a long and vibrant history of humanitarian aid work in the desert, the combination of arrests, raids, and prosecutions has had a profound effect. When asked to describe the current state of relations between those groups and law enforcement, Reineke, the veteran anthropologist at Colibrí, offered two words: “Completely broken.”

Image: USA v. Deighan et al

In addition to the exhibits the government would like to have sealed, the motions filed this week provide the latest evidence that law enforcement actions taken against No More Deaths, an official ministry of the Unitarian Universalist Church in Tucson, are part of a campaign targeting the organization. In a sworn declaration, Robin Reineke, a cultural anthropologist and director of the Colibrí Center for Human Rights, an internationally renowned organization that repatriates the remains of migrants who die in the desert, described a meeting last summer in which a senior Border Patrol agent angrily told her that because of the bad press No More Deaths stirred up for his employer, the agency’s plan was to “shut them down.”

In an interview with The Intercept on Wednesday, Reineke described the meeting as “disturbing,” saying it spoke to a broader breakdown between nongovernmental organizations responding to the humanitarian crisis on the border and federal law enforcement, including a Border Patrol workforce emboldened by an administration set on pushing an already punishing immigration enforcement apparatus into overdrive.

Photo: Laura Saunders for The Intercept

Big and Wild

Currently, nine volunteers with No More Deaths are fighting federal charges for their work providing water and medical care in the Sonoran Desert, historically one of the most lethal migrant passageways on the planet. The most serious of those charges, including harboring and conspiracy, have been leveled against Scott Warren, an instructor at Arizona State University. Warren stands accused of providing two undocumented men with food, water, and a place to sleep over three days. He faces 20 years in prison if convicted. In addition to the felony case, Warren is one of nine No More Deaths volunteers to be hit with federal misdemeanor charges for humanitarian work on the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge over the last year.The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service itself describes Cabeza Prieta as “big and wild” and “incredibly hostile to those that need water to survive,” with a “56-mile border with Sonora, Mexico, [that] might well be the loneliest international boundary on the continent.” According to the Office of the Medical Examiner in Pima County, 33 sets of human remains were found on the refuge last year alone, adding to the more than 8,000 sets of human remains found along the border since the U.S. government began funneling migrants into the desert over two decades ago.

In the case in question, four No More Deaths volunteers — Caitlin Deighan, Zoe Anderson, Logan Hollarsmith, and Rebecca Katie Grossman-Richeimer — say they were doing everything in their power to prevent that grim toll from expanding when they were targeted by law enforcement.

On July 19, No More Deaths received a distress call from a woman in Phoenix reporting that two of her cousins and a friend were in need of help on the refuge. Volunteer Jesse Ferrell filled out the intake form. The woman told Ferrell that the group had built a bonfire to attract help the previous night and that by the following morning, they had run out of water. The men called the Mexican consulate in Tucson, the woman said, and were told to call 911. They did so, she added, but were told by the operator that nothing could be done. They would need to communicate with an immigration-specific office.

In Arizona, the Border Patrol’s Missing Migrant Initiative requires 911 dispatchers to transfer calls from migrants in the desert to a Joint Intelligence and Operations Center in Tucson. For years, the MMI program has been managed by two agents in the Border Patrol’s Tucson sector: Mario Agundez and Pedro Alonso Jr. The documents submitted in court this week show Ferrell first emailing Agundez at 1:57 p.m., then again roughly a half-hour later, at which point Agundez was told that the migrants were at a well-known peak as recently as the previous night, and that they were out of water. The email thread indicates Agundez first responded to No More Deaths more than seven hours after the group’s initial email was sent.

According to Reineke, slow responses to distress calls have become standard with the Border Patrol, and with Agundez specifically. In the declaration she submitted this week, Reineke explained that in years past, her organization “worked closely” with agents from the Border Patrol’s Search, Trauma, and Rescue teams, otherwise known as BORSTAR. “Over time, however, we learned that BORSTAR was generally unresponsive to calls for distress,” Reineke said. “Even in cases of a distressed migrant who had been seen within an hour of the rescue call.”

It was the same in cases where Border Patrol was provided a map of the migrant’s last known location, Reineke added. “BORSTAR would not initiate search and rescue operations — at times affirmatively denying the request to us in writing, and at other times simply not responding to the request.” Based out of the Office of the Medical Examiner in Pima County, the team at Colibrí stopped forwarding distress calls to BORSTAR in 2015, Reineke said, in part because of a “particularly poignant” case in which Agundez reportedly refused a desperate wife’s request to initiate a search for her husband.

In place of BORSTAR, Reineke said, Colibrí began forwarding its distress calls to No More Deaths. Recently, she explained, she has observed a marked change in the Border Patrol’s treatment of the organization. On June 12, 2017, the Border Patrol raided a camp that No More Deaths has used to provide medical aid for migrants for more than a decade, following a tense three-day standoff and leaving with five undocumented men it had tracked to the location in tow. As The Intercept reported at the time, No More Deaths volunteers saw the operation as a message from the Border Patrol that things would be different under the Trump administration. Reineke happened to have a prescheduled meeting with Agundez and his partner, Alonso, a week after the raid took place.

“I expressed my anger and dismay that agents would raid a humanitarian aid station in the desert during a heatwave,” Reineke said in her declaration. Agundez’s response was “angry” and “defensive,” she said. “He referred to the negative press against the Border Patrol generated by No More Deaths, and said they had ‘gone too far,’ that ‘they have messed with the wrong guy.’” Reineke added, “He told me the agency had intentions to ‘shut them down.’”

In an interview Wednesday, Reineke told The Intercept that she had called for the June 21 meeting with Agundez and Alonso Jr. after receiving upsetting reports from officials at two Latin American consulates that the Border Patrol had been discouraging them from cooperating with Colibrí. It was in that tense context, Reineke said, that the Border Patrol’s raid on the humanitarian aid camp came up. Agundez’s response left Reineke with a clear impression. “My impression was hostility to No More Deaths,” she said.

“I got a really strong sense of retribution, revenge — he didn’t like what No More Deaths was saying to the press about Border Patrol,” she added. “I really got the strong impression that he wanted to see the camp shut down and gone.”

Unauthorized Driving

When the four No More Deaths volunteers entered the Cabeza refuge last July, they were followed by a Border Patrol agent. A senior refuge official overheard what was happening via radio and called a Fish and Wildlife officer to respond. As this week’s motions note, both sides in the case acknowledge that the No More Deaths volunteers, once stopped by law enforcement, explained that they were on the refuge in search of three people in distress, that they lacked permits, and that they “did not see the signs labeling the road as an administrative road because they were in a hurry to search for the three distressed individuals.”More than five months would pass before the government formally charged the group with federal misdemeanors related to unauthorized driving and entering the refuge without a permit. Ultimately, two of the migrants reported missing were found by a pair of Border Patrol agents stationed in Ajo, Arizona, and a Yuma-based Customs and Border Protections helicopter crew that established communications with the No More Deaths volunteers. The third individual was never found.

Although charges were not brought for months, Cabeza Prieta officials did not waste time in flagging the No More Deaths volunteers as troublemakers. According to internal communications obtained by The Intercept via a Freedom of Information Act request, Mary Kralovec, then-assistant refuge manager at Cabeza Prieta, sent an email to colleagues and counterparts at the Fish and Wildlife Service and the Air Force (which manages the nearby Barry Goldwater bombing range), the day after the rescue operation, highlighting the four volunteers as “individuals who we are not issuing access permits to.”

A little more than a week later, on July 28, Margot Bissell, a visitor services specialist at Cabeza Prieta, began sending a series of text messages that are now at the center of the disclosure fight in the No More Deaths volunteers’ case. According to the motions filed this week, Bissell’s messages were sent to a Border Patrol agent who at this point remains unnamed. The exchange begins with Bissell writing, “Cry me a river – me too,” followed by a laughing emoji. While the context of the comment is unclear, the following message is not.

“They have been very quiet since we started action against them … Until last week,” Bissell wrote. She then asked, “Did you hear about the group at the Charlie Bell well?” — referring to the location where the No More Deaths volunteers were encountered.

“Oh yeah,” the agent replied. “That really sparked everything back up.”

Image: USA v. Deighan et al

“Sweet,” the agent replied. “You got any new info or names.” Whether Bissell replied is unclear.

An email to Bissell’s work address seeking comment on her texts generated an out of office reply. Her supervisor, Sid Slone, did not respond to a request for comment.

The disclosure of the text messages comes three months after The Intercept was first to report on a series of communications and internal reports between Border Patrol agents involved in Warren’s felony arrest. Those materials included talk of an open investigation into No More Deaths as an organization and cited the raid on the No More Deaths camp that Agundez referenced with Reineke as the beginning of that effort.

The inclusion of those communications in pretrial motions, which also included law enforcement text messages, angered Trump administration attorneys: In the words of one individual close to the case, the government’s attorneys were “fucking pissed.” The prosecutors successfully lobbied to have the materials sealed after The Intercept reached out to Justice Department for comment, but before the article was published.

Selective Prosecution

For attorneys representing the No More Deaths volunteers, there is now little question that federal law enforcement in southern Arizona has taken a particular interest in targeting the organization. In addition to Reineke’s declaration, Fish and Wildlife Service records obtained by the lawyers, included in this week’s motions, revealed that from 2015 to 2018, agents with the land management agency issued 14 citations for various violations of federal regulations or law in the Cabeza Prieta refuge.“None of these incidents were referred for prosecution or prosecuted, except for those involving No More Deaths volunteers,” the attorneys noted, including the four defendants cited in connection with last summer’s search and rescue operation.

Other groups that do search and rescue work were not similarly cited, the lawyers added. The difference between No More Deaths and those organizations, they argued, is that No More Deaths publicly critiques the Border Patrol and U.S. border enforcement policies. “Thus,” attorneys for the volunteers contended, the Fish and Wildlife Service’s “own records indicate that defendants were subject to enforcement action as a result of their affiliation with an organization speaking out against the government’s immigration policies and conduct.”

Last summer, as the number of remains recovered on Cabeza Prieta reached record highs, land managers tweaked permit applications for the refuge, requiring applicants to explicitly agree to not leave food, water, or clothing on the refuge. No More Deaths saw the change as a direct attempt to undermine their efforts to provide lifesaving aid in a place where people are clearly dying. Their attorneys say the change was illegitimate, arguing that the land managers failed to publish the new permit language in the federal register, “nor was it subject to public notice and comment procedures as required by the Fish and Wildlife Service Manual and the Code of Federal Regulations governing the Service’s rulemaking.”

The enforcement of permitting rules stemming from “illegally-amended language” against No More Deaths volunteers alone amounts to violation of an international smuggling protocol the U.S. ratified in 2005, the attorneys say. The protocol requires that the state cooperate with nongovernmental organizations “in protecting and preserving the human rights of smuggled migrants,” the attorneys noted. But it goes deeper than that, they argued. By seeking to imprison a group of humanitarian volunteers over their efforts to save three people in the desert, the state had entered into dark territory reserved for the worst regimes, the attorneys contended.

“Common decency requires that a government do what it can to prevent unnecessary death and suffering inside its borders,” the lawyers argued in the motions filed this week. “To actively thwart efforts of its citizens to assist those in need through the provision of the most basic necessities — emergency food and water — is cruel and shameful behavior. And to threaten to imprison citizens for searching for distressed migrants stranded in highly dangerous locations — generous, humane actions the government should encourage and applaud — is unconscionable. It violates the universal sense of justice.”

In the southern Arizona, a place with a long and vibrant history of humanitarian aid work in the desert, the combination of arrests, raids, and prosecutions has had a profound effect. When asked to describe the current state of relations between those groups and law enforcement, Reineke, the veteran anthropologist at Colibrí, offered two words: “Completely broken.”

Top photo: The U.S. Customs and Border Protection station in Ajo, Ariz.

copy https://theintercept.com

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário