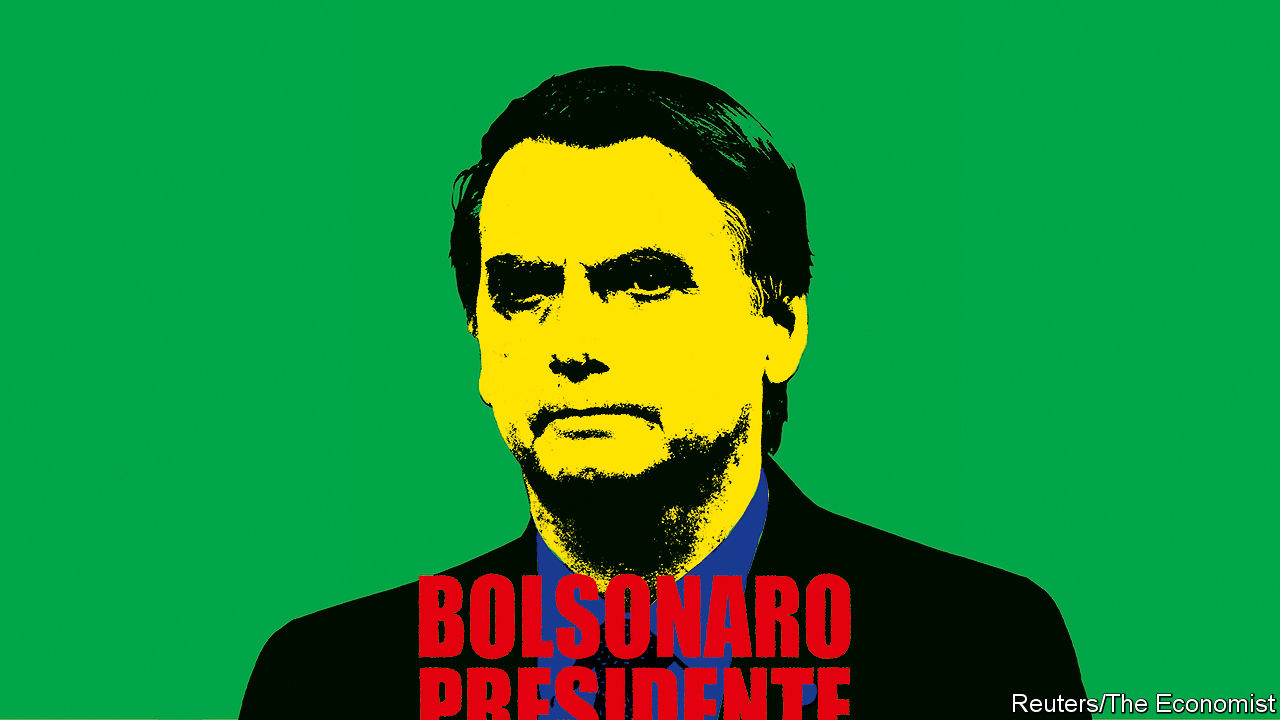

Brazil’s presidential electionJair Bolsonaro, Latin America’s latest menace

He would make a disastrous president

GOD is Brazilian,” goes a saying that became the title of a popular

film. Brazil’s beauty, natural wealth and music often make it seem

uniquely blessed. But these days Brazilians must wonder whether, like

the deity in the film, God has gone on holiday. The economy is a

disaster, the public finances are under strain and politics are

thoroughly rotten. Street crime is rising, too. Seven Brazilian cities

feature in the world’s 20 most violent.The national elections next month give Brazil the chance to start afresh. Yet if, as seems all too possible, victory goes to Jair Bolsonaro, a right-wing populist, they risk making everything worse. Mr Bolsonaro, whose middle name is Messias, or “Messiah”, promises salvation; in fact, he is a menace to Brazil and to Latin America.

Mr Bolsonaro is the latest in a parade of populists—from Donald Trump in America, to Rodrigo Duterte in the Philippines and a left-right coalition featuring Matteo Salvini in Italy. In Latin America, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, a left-wing firebrand, will take office in Mexico in December. Mr Bolsonaro would be a particularly nasty addition to the club (see Briefing). Were he to win, it might put the very survival of democracy in Latin America’s largest country at risk.

Brazilian bitterness

Populists

draw on similar grievances. A failing economy is one—and in Brazil the

failure has been catastrophic. In the worst recession in its history,

GDP per person shrank by 10% in 2014-16 and has yet to recover. The

unemployment rate is 12%. The whiff of elite self-dealing and corruption

is another grievance—and in Brazil it is a stench. The interlocking

investigations known as Lava Jato (Car Wash) have discredited the entire

political class. Scores of politicians are under investigation. Michel

Temer, who became Brazil’s president in 2016 after his predecessor,

Dilma Rousseff, was impeached on unrelated charges, has avoided trial by

the supreme court only because congress voted to spare him. Luiz Inácio

Lula da Silva, another former president, was jailed for corruption and

disqualified from running in the election. Brazilians tell pollsters

that the words which best sum up their country are “corruption”, “shame”

and “disappointment”.Mr Bolsonaro has exploited their fury brilliantly. Until the Lava Jato scandals, he was an undistinguished seven-term congressman from the state of Rio de Janeiro. He has a long history of being grossly offensive. He said he would not rape a congresswoman because she was “very ugly”; he said he would prefer a dead son to a gay one; and he suggested that people who live in settlements founded by escaped slaves are fat and lazy. Suddenly that willingness to break taboos is being taken as evidence that he is different from the political hacks in the capital city, Brasília.

To Brazilians desperate to rid themselves of corrupt politicians and murderous drug dealers, Mr Bolsonaro presents himself as a no-nonsense sheriff. An evangelical Christian, he mixes social conservatism with economic liberalism, to which he has recently converted. His main economic adviser is Paulo Guedes, who was educated at the University of Chicago, a bastion of free-market ideas. He favours the privatisation of all Brazil’s state-owned companies and “brutal” simplification of taxes. Mr Bolsonaro proposes to slash the number of ministries from 29 to 15, and to put generals in charge of some of them.

His formula is winning support. Polls give him 28% of the vote and he is the clear front-runner in a crowded field for the first round of the elections on October 7th. This month he was stabbed in the stomach at a rally, which put him in hospital. That only made him more popular—and shielded him from closer scrutiny by the media and his opponents. If he faces Fernando Haddad, the nominee of Lula’s left-wing Workers’ Party (PT) in the second round at the end of the month, many middle- and upper-class voters, who blame Lula and the PT above all for Brazil’s troubles, could be driven into his arms.

The Pinochet temptation

They

should not be fooled. In addition to his illiberal social views, Mr

Bolsonaro has a worrying admiration for dictatorship. He dedicated his

vote to impeach Ms Rousseff to the commander of a unit responsible for

500 cases of torture and 40 murders under the military regime, which

governed Brazil from 1964 to 1985. Mr Bolsonaro’s running-mate is

Hamilton Mourão, a retired general, who last year, while in uniform,

mused that the army might intervene to solve Brazil’s problems. Mr

Bolsonaro’s answer to crime is, in effect, to kill more

criminals—though, in 2016, police killed over 4,000 people.Latin America has experimented before with mixing authoritarian politics and liberal economics. Augusto Pinochet, a brutal ruler of Chile between 1973 and 1990, was advised by the free-marketeer “Chicago boys”. They helped lay the ground for today’s relative prosperity in Chile, but at terrible human and social cost. Brazilians have a fatalism about corruption, summed up in the phrase “rouba, mas faz” (“he steals, but he acts”). They should not fall for Mr Bolsonaro—whose dictum might be “they tortured, but they acted”. Latin America has known all sorts of strongmen, most of them awful. For recent proof, look only to the disasters in Venezuela and Nicaragua.

Mr Bolsonaro might not be able to convert his populism into Pinochet-style dictatorship even if he wanted to. But Brazil’s democracy is still young. Even a flirtation with authoritarianism is worrying. All Brazilian presidents need a coalition in congress to pass legislation. Mr Bolsonaro has few political friends. To govern, he could be driven to degrade politics still further, potentially paving the way for someone still worse.

Instead of falling for the vain promises of a dangerous politician in the hope that he can solve all their problems, Brazilians should realise that the task of healing their democracy and reforming their economy will be neither easy nor quick. Some progress has been made—such as a ban on corporate donations to parties and a freeze on federal spending. A lot more reform is needed. Mr Bolsonaro is not the man to provide it.

copy https://www.economist.com/

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário